Katya Cherukumilli first became concerned about lead in drinking water in Washington schools after reading a 2019 article in the Seattle Times reporting that 97 percent of schools participating in a voluntary testing program had at least one fixture producing water with levels of lead higher than the one part per billion threshold recommended by the American Association of Pediatrics.

Intrigued, Cherukumilli, who is an assistant professor in the Department of Human Centered Design and Engineering, said she started playing around to see what public data was available. “It was a coincidence,” she said, “I was curious whether there were any grants at the state or federal level to deal with this issue, and then I came across the OSPI [Washington Office of Superintendent of Public Instruction] page for their grant program and I immediately e-mailed the program manager to learn more.”

It turns out that most school districts weren’t applying for funds available to help remediate lead in school drinking water. In 2021-2023, for example, the state had $3.47 million to give for remediating lead in drinking water in schools. Only eight districts applied and $3.1 million went back to the state.

The OSPI grant program manager said they didn’t know why school districts weren’t applying. “It could be a communication issue, and schools don’t know this money exists,” Cherukumilli explained. “It could be that they never had testing done so they’re not eligible. It could be that they don’t have the bandwidth and are more concerned about first addressing school safety, air pollution, heat, or other higher priority issues. But, until we know the reason, we can’t help.”

Seeing an opportunity

Cherukumilli saw an opportunity to contribute. “This project just felt like a perfect overlap, since I’m an environmental engineer working in human centered design, I think a lot about the contexts in which technologies are deployed and the barriers faced by potential users to accomplish their end goals. To me, the problem of lead contamination in schools poses an interesting engineering, science communication, and environmental health challenge.”

In early spring of 2025, Cherukumilli received a $50,000 pilot grant from the UW Interdisciplinary Center for Exposures, Diseases, Genomics and Environment (EDGE) to fund her lab’s work on lead with Washington schools.

Currently, she oversees a team of undergraduate researchers who are busy cleaning up data on lead and drinking water collected by the Washington Department of Health (DOH) and related data from OSPI on schools—including the year they were built or retrofitted—and on the students themselves—including household income, language spoken at home, age, race, and standardized test scores.

Characterizing risk

Cherukumilli and her team are working to create a broad picture of lead exposure for school kids that includes more than just water at school. Their exposure mapping encompasses even the number of flights of small aircraft over King County schools using data from Elena Austin, assistant professor in the UW Department of Environmental and Occupational Health Sciences (DEOHS) and co-director of EDGE's Exposure Assessment Biomarkers and Environmental Sensing Facility (EABES) Core. Unlike large commercial jets, small aircraft are still allowed to use leaded fuel.

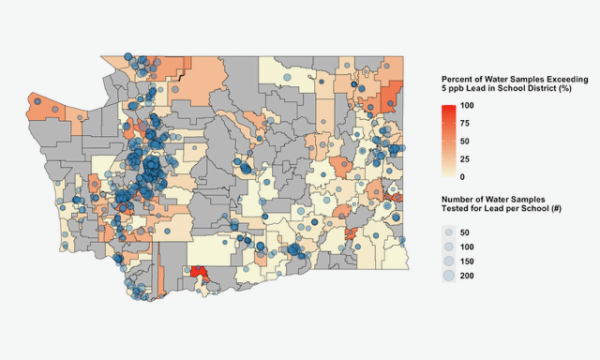

“The whole point of this effort—collecting, cleaning, aggregating, and mapping different datasets—is to identify which school districts, schools, and students are at highest risk of lead exposure through drinking water in WA state,” said Cherukumilli. “Through our data analysis, we will identify and prioritize high-risk school districts to contact. Our team will inquire if these districts applied for remediation funding or if they require any help in accessing and using resources to mitigate the lead contamination issue.”

Understanding the barriers

Understanding the barriers that keep school districts from applying for funding to remediate the lead in their drinking water is the second focus of Cherukumilli’s pilot project. Later this year, her doctoral student will send online surveys to officials in almost 300 school district superintendent offices to better understand their priorities with regards to environmental health issues. In parallel to the online survey, her team plans to start by conducting one-on-one interviews with some of the school district officials who have already applied for OSPI funding to remediate lead in school drinking water.

“We want to understand what motivated these districts to apply, how difficult the grant application process was, how they used the money, and then assess their willingness to share their experience with other districts,” explained Cherukumilli. Later, the team will schedule follow-up interviews with the high risk districts that have not yet applied.

Gaps in the data

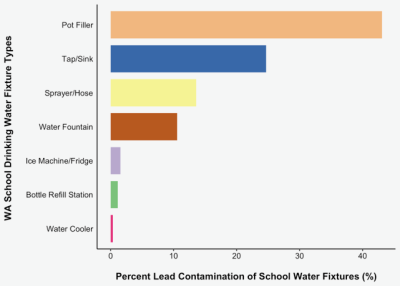

“One thing I’m realizing as we’re analyzing the data,” said Cherukumilli, “is that a lot of school districts are just missing data on drinking water quality.” So far, the WA DOH has conducted water lead testing in about 65% of the state’s school districts, she says, and maybe in about one quarter of the schools in the state (Figure 2). This finding has inspired Cherukumilli’s team to reach out to school districts with no lead testing data to see if they could help with sampling (and future remediation) efforts.

Cherukumilli recently won funding from the UW Campus Sustainability Fund to do water quality testing on the UW campus and has 200 bottles sitting in her office waiting for rapid testing from a state-accredited lab. She says it might be possible to sample other water sources the same way.

At the same time, Cherukumilli’s lab also received a UW Student Technology Fee (STF) grant to purchase two X-ray Fluorescence (XRF) devices that can be used to characterize the elemental composition of liquid and solid materials, including measuring toxic contaminants such as lead, arsenic, mercury, and uranium.

Collaborations

Chris Simpson, a professor in DEOHS and the director of EDGE’s EABES Core, and Anne Riederer, a clinical associate professor in DEOHS, have been discussing opportunities to collaborate with Cherukumilli on using XRF devices to measure fluoride and iodide in maternal urine in an ongoing pregnancy cohort study. In addition, they connected her with Diana Ceballos, an EDGE member and assistant professor in DEOHS, who is developing novel methods using XRF for measurement of per-and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS). PFAS are otherwise known as “forever chemicals” because of their ability to persist in the environment for long periods without breaking down.

Students working with Cherukumilli this summer are visiting the Ceballos lab to learn about their PFAS experiments, conducting literature reviews to identify knowledge gaps for measurement of other contaminants in drinking water and human biomarkers, and beginning to develop and test new XRF protocols in the lab.

The end goal

In the end, Cherukumilli hopes to be able to take her combined results to OSPI and DOH to encourage them to improve how WA school districts are required to apply. They may, for example, develop online tools that provide school districts with the necessary information to apply. Ideally this will result in more applicants, more money going to districts, and, ultimately, less lead in school drinking water.

“There’s a huge amount of data showing how improvements in drinking water infrastructure are connected directly to children’s health and student outcomes,” said Cherukumilli. “The evidence strongly suggests that water treatment and control of lead in water is a worthwhile investment.”

- Community Engagement

- Exposure Sciences

- Environmental Justice/ Environmental Health Disparities